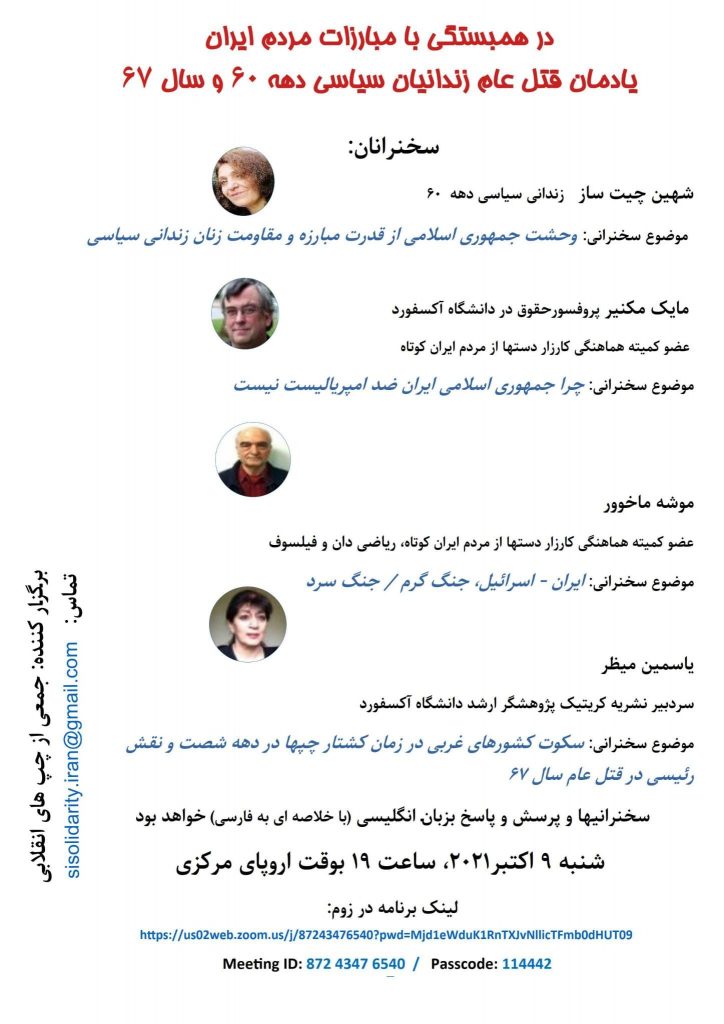

On October 9 a group of Iranian revolutionaries, now mainly based in North America and Europe, organised an online meeting to commemorate the 1988 massacre of political prisoners. Among the speakers were Yassamine Mather, Shahin Chitsaz and Mike Macnair

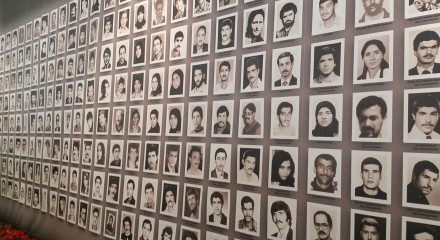

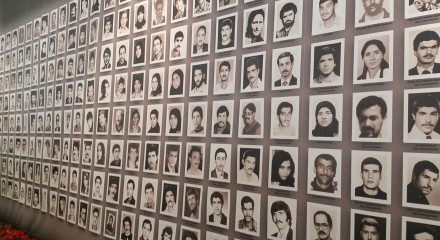

Mass executions of political prisoners began in July 1988 and carried on for five months. No-one can be certain of how many died, but the total must run into many thousands

In recent years – especially since the start of the nuclear confrontations/negotiations between Iran’s Islamic Republic and western governments – the plight of political prisoners, tortured in Iranian prisons, as well as those executed by the Iranian regime, has gained prominence.

The Trump and Biden administrations in the US, as well as those in several European countries, have suddenly realised that the current Iranian president, Ebrahim Raisi (who became head of the judiciary in 2019 before his ‘election’ as president this year), was personally involved in the mass execution of Iranian political prisoners in the 1980s. This is ironic, since from the time of those executions until the recent nuclear debacle, the imperialist powers could not have cared less about the fate of leftwing political prisoners in Iran. In fact claims of concerns expressed by such governments in relation to ‘human rights’ in Iran or anywhere else are always directly linked to imperialist interests. Obedient allies are exempt from any such concern. For example, currently Saudi Arabia and Israel are hardly mentioned when it comes to ‘human rights violations’. In fact it is amazing that after all the revelations about the USA’s own record in Guantanamo, Abu Ghraib, etc, anyone could believe the west’s ‘concern for human rights’. Yet, despite this, even some Iranians who claim to be leftwing still have illusions in the possible role of the US and its allies in replacing the current regime.

The execution of leftwing political prisoners in Iran in the early 1980s was of little interest to western governments. They had considered the entire opposition to the shah as a threat to their own interests and, following his overthrow in the 1979 revolution, they considered an Islamic government in Tehran to be a better option than the continuation of the mass unrest, which could have resulted in much greater influence for the ‘official communists’. That was still during the cold war, of course, so the fact that that the Islamic government was executing leftwingers was, as far they were concerned, for the best.

There were far more important issues to worry about: the taking of hostages in the US embassy in Tehran; the ex-shah’s travels in search of sanctuary; the start of the war with Iraq. Hopefully Saddam Hussein’s forces were going to bring down the Iranian regime. The Islamic Republic’s human rights record did not matter an iota in this context. For example, supreme leader Ruhollah Khomeini’s fatwa against the Kurdish people dates back to this period, but no western government batted an eyelid.

When it comes to the late 1980s, let us remember the political context of the relations between Iran and western governments in this period. The years 1985-87 coincide with what was called ‘Irangate’ or the ‘Iran contra affair’. This was a political scandal in the US that occurred during the second term of the Reagan administration, when senior officials secretly facilitated the sale of arms to the Islamic Republic, despite an official embargo. The administration wanted to use the proceeds of the arms sale to fund the Contras in Nicaragua.

August 1988 saw the end of the Iran-Iraq war after Khomeini had, in his own words, “drunk the poison” of signing a peace agreement with Saddam Hussein, who was considered a major US ally at the time. Iran was now embarking on post-war ‘reconstruction’ and European firms were eager to enter into economic trade and development deals with Tehran, so ‘human rights’ was the last thing they were worried about.

A series of state-sponsored executions of political prisoners across Iran started in July 1988 and lasted for approximately five months. While the exact number of those killed remains something of a mystery, there is no doubt that the figure runs into the thousands.

Shortly before the executions commenced, Khomeini issued a secret order to set up ‘special commissions’ with instructions to execute members of the People’s Mojahedin Organisation of Iran as mohareb (those who war against Allah) and other leftwingers as mortad (apostates from Islam).

The “treacherous” Mojahedin “do not believe in Islam” and they are actually “waging war on god”, as well as “collaborating with the Ba’athist Party of Iraq” and “spying for Saddam against our Muslim nation”. It was therefore decreed that those prisoners who “remain steadfast” in their support for the Mojahedin are “condemned to execution”.

The administration of the executions was implemented by a four-man commission, later known as the ‘death committee’. Members included Ebrahim Raisi, who was then deputy prosecutor general. But it is not just the fact that he was one of the judiciary: it was his signature that appeared on a number of authorising documents. In 2018 Raisi broke his silence on the whole question and publicly defended the mass killings.

Of course, Raisi is not the only guilty party: anyone who had any government or senior religious post in that period knew about the executions, either before they began or shortly afterwards. In other words, all those who have been in power since the late 1980s or who are currently in power – including those who belong to the ‘reformist’ faction of the regime – are also responsible.

Yassamine Mather

Witness

I first encountered Raisi on August 31 1988 in a so-called ‘court’ that was issuing death sentences for political prisoners. I faced my accusers, who, seated from left to right, were:

- Prosecutor Morteza Eshraghi, who is currently an advisor to the judiciary.

- Prosecutor general Hossein-Ali Nayeri, who was in charge of issuing death sentences.

- Ebrahim Raisi, currently Iranian president.

- Another two whose names I do not know.

Next to them was the religious judge.

During the inquisition, Nayeri asked me if I was a Muslim. My initial reply was that I do not answer such questions, as it relates to my private views and I do not intend to be part of any inquisition. The prosecutors insisted that I had to answer and I knew from reports of hangings earlier that day that there was no choice but to give a straightforward political reply. So I tried to remain calm and said: “I have no religion, I am not a Muslim and have never been a Muslim.”

Nayeri continued questioning in a very bad-tempered way and asked me to recite the names of the 12 Shia Imams. I replied that I only knew a few of their names, such as Ali, Hassan and Hossein, and this made Nayeri even angrier, because I had not used the term ‘Imam’ in referring to these people. He rose from his chair and shouted: “Imam Ali, Imam Hossein, Imam Hassan!”

I shrugged my shoulders and within a minute Raisi – the newcomer and second-rate prosecutor – repeated the words of his boss, Eshraghi: “Insulting the Imam is a crime.”

I am making this statement to emphasise that:

- Prisoners who survived, such as myself, witnessed Raisi’s participation as a leading member of the death squads, presiding over the trial of political prisoners.

- Even then he acted very much like the second in command, taking his lead from Nayeri and Eshraghi.

HI

Survivor

I was a political prisoner who survived the massacres of the 1980s. As a member of a Marxist organisation, I was arrested as a student in 1983 and sentenced to three years in prison. I was supposed to be released in 1987, but prisoners had to accept a number of conditions for their release, including the expression of remorse and rejection of the organisation they were affiliated to. However, because I believed that such an act was contrary to the ideals that my comrades and I had fought for – ideals for which many had been imprisoned, tortured or executed – I refused to accept these conditions and remained a prisoner until 1990.

In the bloody decade of the 1980s, many other prisoners did not give up on their politics and were handed over to the death squads. Tens of thousands were buried in unknown mass graves and to this day many families have no information about the fate of their loved ones. Such executions, along with routine torture, cast a shadow over society – anyone who opposed the regime knew what punishment awaited them. The aim was to create an obedient, brainwashed population, with no independent identity.

It should be noted that the regime’s treatment of women, both in prison and outside, is rooted in the sexualisation and misogyny of Islamic ideology, which recognises patriarchal ownership of women’s bodies and minds as an inalienable right. Thus, the large presence of militant and political women in society was contrary to the backward Islamic ideology that called upon women to be obedient. In order to establish Islamic ideology and reproduce religious patriarchy, the regime had to start by suppressing women, forcing them to wear a hijab and to act only as subdued housewives. The biggest obstacle to this gender-based repression was female political activists, who bravely resisted Islamic rule. In fact, the huge wave of active participation of women in the 1979 revolution had frightened the regime.

Here I would like to mention the special circumstances that women prisoners experienced because of their gender. Humiliation, slander and verbal and behavioural sexual harassment were quite common. Contraceptive pills found in revolutionaries’ homes were used to justify attacking women prisoners. In court and during interrogation, women were insulted and humiliated for any reason.

The fear of rape was another psychological form of oppression suffered by women prisoners. Those sentenced to death were said to have been raped before being executed. So, for a girl sentenced to death, the execution she awaited was accompanied by a fear of such rape, which was always present in prison. When we were taken to the dark cells, many were terrified of what might happen to them and some were indeed possibly raped.

Despite the regime’s efforts to rely on the fragility of human beings, resistance under torture to the point of death was common. Neither torture nor solitary confinement and the threat of rape could extinguish the fire of resistance against this regime of murder, looting and oppression.

Between 1983 and 1984, another method of torture used against us was to place women inside coffins – many were forced to sit for long hours inside coffin-shaped boxes. Meanwhile, Quranic verses were played out very loudly over the loudspeaker. At the same time, they were sometimes beaten, punched, kicked and whipped. No speaking was allowed. Prisoners’ use of the toilet was limited to three times a day, under the supervision of guards. Some women lived under conditions of such vicious mistreatment for months, night and day.

In addition, the regime used ‘motherhood in prison’ as a special form of psychological and physical torture against women. Some of the women were pregnant at the time of their arrest, while others were imprisoned along with their newly born child. Pregnant women prisoners were threatened with the handing over of their babies to a Hezbollah family after giving birth, because they were not worthy of caring for their children themselves. This group of women had very miserable experiences during pregnancy, which in some cases led to miscarriage. The fact that they had to raise their children in prison was a terrible trauma in itself, and it caused additional physical, psychological and emotional damage.

When my sentence ended, I became one of the “liberties”. At that time we used that term in prison for those whose sentences had expired, but who did not give up on their principles and thus remained imprisoned. I was released from the custody of judges and sent to closed rooms with more difficult conditions. There were several such closed rooms, where large numbers of prisoners were housed together. We were not allowed to use the toilets more than four times a day, and they were available for only half an hour for 30 to 40 prisoners each time. This short period also had to be used for taking a shower, and for washing dishes and clothes.

A friend of ours, who had protested against the lack of toilet time, was summoned for questioning. Amin Hosseinzadeh, a ministry of intelligence official, told him that steps were being taken to improve our situation and that our problems would be resolved soon. In fact, Hosseinzadeh was a brutal person and had a hand in the massacre of prisoners himself, but at the same time he pretended that the cells would soon open up and our problems would be reduced!

We were in the same closed rooms for several months, and in July 1988 several armed guards came in and ordered us all to wear a hijab. We were all asked which organisation we belonged to. Those whom they disliked, or those named in the reports given to them by prison guards, were ordered to leave the room and wait. I was one of them and we were all taken to an isolation cell.

A prisoner next to my cell, who had had access to a newspaper, informed me that the regime had accepted a ceasefire with Iraq. I heard from another prisoner that a group of young women from the Mojahedin had been secretly executed. But in general our connections to the outside world were cut off – no newspapers, no visiting, and those who were sick were not even taken to the prison’s health centre.

A few weeks later I and a few others were taken from solitary confinement to the ‘court’, which was made up of a handful of people who decided our fate following a few questions related to our political positions and beliefs. The prisoners called it the ‘Death Squad’.

I was asked once again whether I was a Muslim or not and I answered no. They then asked if my father was a Muslim, to which I answered that he was. They asked my opinion about the Islamic Republic and I replied that I did not accept this regime. They asked if I prayed, but, of course, my answer was no.

After these questions, they issued me with the following sentence: I would be subjected to five lashes several times a day until I agreed to become a Muslim. This so-called ‘trial’ did not last more than two or three minutes in the presence of a delegation whose members had been appointed by the supreme leader, Ruhollah Khomeini. I was handed over to the guard, who was told: “Her sentence is flogging, from today.”

I was sent back to the cell. The sound of food carts could be heard from the hallway. It was not until a few minutes later that the guard opened the cell and took me out. I managed to see under my blindfold that my friends were lined up in the hallway. We were all taken blindfolded to the torture chamber, while the sound of the Quran could be heard from the speaker. We reached the prison room where there was a wooden bench, next to which some women guards were standing. The women inspected our bodies to make sure we were not wearing extra clothes to give us some protection from the whipping. I was asked yet again, “Are you a Muslim? Do you pray?” Again, the answer was no. The official – a man called Mojtaba Halvaei – shouted: “Sleep on the couch!” and I lay on my stomach on the bench. Halvaei started to whip my back with a cable, hitting me very hard five times. With each blow, it was as if the whole of my being was on fire and being torn apart. Then they took me back to the cell.

I could hear the sound of the cable and the shouts of my friends from inside the cell. This was about midday and all my muscles were contracted, but at around three or four o’clock in the afternoon I was given another flogging. The next after that was at dusk, then later in the evening, and again at four o’clock in the morning. Five times a day I was subjected to this flogging – five strokes with the cable each time, a total of 25 per day. For 14 endless days this first series of cruel and misogynistic torture went on – all to demonstrate that women had no right to intellectual independence, let alone political opposition.

Everyone tried to bear it as much as they could, but several people committed suicide. For others it was even worse. Other women were subjected to the same torture, which lasted for 22 days – a total of 550 lashes. Some went on hunger strike in protest. The end was death, unless you accepted that you were a Muslim. There was no time to relax or even sleep. The whole time was spent either suffering a cable lashing or waiting for it! Then you could hear the sound of your friends being flogged, against the background of the Quran playing continuously.

One day I heard other horrible noises. The Revolutionary Guards were parading outside, accompanied by cries of Allahu Akbar (‘God is great’). There was a boiler tube in the corner of one of the cell walls and it was possible to climb on top of it, from where I could just about see out of the cell window, which was covered with iron railings. I saw the male prisoners being lined up and taken away. Their eyes were covered and everyone was holding the shoulder of the person in front. They sang hymns, but within minutes I heard gunshots. I was filled with fear, panic and a sense of helplessness. I was overwhelmed with grief and anxiety.

I never thought I would come out of this house of terror alive, but at the same time the resistance of fellow prisoners warmed my heart – they were dying for their human ideals. They responded to the humiliation of death with the love of life.

During all this time, all our communication channels with the outside world had been cut off, but by the end of 1989 visits were permitted – but not for everyone. Many families were informed of their loved one’s execution and received their belongings instead of visiting them!

Gradually, I realised that all the other Mojahedin women who had been held in closed rooms had been executed. I had not known the scale of the tragedy, which involved the slaughter of thousands of prisoners in the days when I was held in a closed cell.

All of this is in fact just the tip of the iceberg, when it comes to the regime’s crimes against its opponents. The Islamic Republic has tried for many years not to reveal the extent of these crimes. They closed the Khavarans (mass graves) to the families of those executed, maintaining a deadly silence about this genocide.

What is our task now? Each of us, bearing the souls of the bereaved, is demanding to hear the full extent of these crimes. These efforts have not been and will not be ineffective. The world should not forget and forgive what has happened and is still happening, if we are to prevent history from repeating itself. Anyone who remains silent about these crimes will be responsible and accountable to humanity throughout history. In the words of holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel, “Silence always helps the oppressor, not the oppressed.”

Shahin Chitsaz

Fake anti-imperialism of Islamic republic

The anti-US rhetoric of the Islamists has led many leftwingers to think of them as in some sense anti-imperialists. This was already present in 1979-80 – I am old enough to remember debating the issue in the International Marxist Group-Socialist League at that time. Even though I understood that the Afghan Mojahedin were reactionaries, I shared the Fourth International majority view that the Islamists represented a form of nationalism, and that the logic of ‘permanent revolution’ would drive them towards anti-imperialism.

There was a limited degree of plausibility then of this view – at least in the ‘official communist’ version, in which ‘anti-imperialism’ led to geopolitical alignment with the USSR. But it was already highly questionable in the light of the integration of many nationalist groups into the imperialist world order and the price which communists and labour activists had repeatedly paid for trust in these forces. Once the USSR fell, the plausibility of reasoning of this sort diminished to near zero. But leftwingers have nonetheless clung on to it: it was a recurrent theme in left arguments in Britain within the Stop the War Coalition.

I take it at the outset that believers in Islamist anti-imperialism are right to think that Islamists of the type of the Iranian regime (or of the current Turkish government) are, in fact, a kind of nationalist – one which places more value on patriarchalism and national-cultural tradition than liberal or leftist nationalism, to be sure, but this was true equally of the German Romantic or Spanish clericalist anti-French nationalism of the Napoleonic period.

I specify further that, although they promote anti-US and anti-‘westernising’ rhetoric, the Islamists are not socialist or anti-capitalist: this is clear enough from their conduct in government. They could have been genuinely anti-capitalist in a reactionary sense: in the sense of seeking to eliminate large-scale industry, drive the city-dwellers into the countryside and restore the old landlord-clerical regime. We can perhaps think of the Khmer Rouge as pursuing this policy in 1975-76. But in fact there is no sign of any such de-modernisation. The Iranian regime has created, if anything, a state crony capitalism of a sort not uncommon in semi-colonial countries (and currently spreading into the imperialist centres, as in the cronyism of the current British Tory government). Where it happens in the modern world, de-modernisation results from US military interventions, not voluntary choices of conservatives.

Finally, by ‘imperialism’ I mean specifically a global regime in which some countries are held in subordination to other countries for the benefit of the economies of the ‘imperial’ countries: thus contrasting with ancient empires, which spread more or less uniform culture and relations of production within their state territories, though holding borders against outside barbarians, and with feudal territorial expansionism driven by landlord and peasant land-hunger (like the German Drang nach Osten, Iberian Reconquista, and English expansion into Wales and Ireland). Political subordination serves economic subordination, whether directly or indirectly. Thus, for example, US sanctions against Iran are to a considerable extent about holding China, France and Germany in subordination to the USA.

The question, then, is whether nationalism which is not socialist is capable of being anti-imperialist. My answer is that it is not; and the explanation is that there is no such thing in the world as a capitalism which is not located within an international capitalist hierarchical order of countries: that is, within the framework of imperialism.

Capitalism came into the world centred on the bulk-shipping industry of the late middle ages: primarily in the Mediterranean interfaces of Christendom and the Dar-al-Islam, but secondarily in the North Sea area. Capital is the circuit, M-C-P-C′-M′, where P is carried out by organised groups of wage-workers adapted to the needs of high-capital-value machinery, as opposed to being carried out on a domestic or family scale. Capitalism involves, as a result, both the freedom and equality of market relations, and the concentrated authority of the factory. Hence it throws up both libertarian and authoritarian-traditionalist political forms.

The large ship – and the docks it works between – are early cases of this arrangement. Bulk shipping is not the only medieval form of this, but it is the one that remakes the world. The shipping capitalists subordinated to themselves both the production of raw materials at one end and ‘working them up’ for consumer sale at the other. Thus bulk-shipping merchants controlled both supply and demand for worked-up goods, so as to create ‘putting-out’ manufacture or ‘proto-industry’. At the other end, we get Venetian slave-worked sugar plantations on Cyprus and Crete, Genoese on the Canaries, Portuguese on further Atlantic islands and Brazil, Dutch on Taiwan and so on; and in the 1600s Dutch demand for grain supported ‘second serfdom’ in eastern Europe.

In other words, capitalism has always been imperialist.

Then there is money. “I promise to pay the bearer on demand the sum of £5 London: for the Governor and Company of the Bank of England, signed NN Chief Cashier.” This is, of course, a lie – the object is a plastic token prescribed by the UK state to be legal tender, and the form of words a mere piece of British antiquity-cult. But in origin the banknote was a promissory note issued by the Bank of England, and all sorts of people could and did issue such notes, enforceable under the Promissory Notes Act 1704.

What lies behind this is that there is insufficient gold, silver and copper in the world for the transactions needs of a late-medieval economy, let alone that of an economy in which the circuit of capital becomes the general form of organising production. Late medieval and early modern economies worked to a considerable extent on the alternative of interpersonal credit – that is, the farmer runs a tab (a credit account) with the local shoemaker, to be paid off at harvest time; the shoemaker himself runs a tab with the local butcher, and so on. But this sort of operation was usually on an insufficient scale for actual capitalist operations. Bills of exchange, promissory notes and other such instruments are those of impersonal credit. They work because the state makes the transferable debt instrument enforceable by the transferee without regard to the underlying transaction – ‘negotiability’ (though what I have just said is a simplification).

Why don’t debtors just default and run away? The answer is that the state which backs the transferable debt instrument discriminates against foreign traders, and this discrimination is sufficient – outside of actual insolvency – to incentivise debtors in general to pay their debts; and the result is that transferable debt instruments enforceable by a sufficiently strong state can be used as money, not merely within that state, but internationally. Thus ‘bills on Amsterdam’ in the 17th century, ‘bills on London’ in the 19th, and dollar instruments in the later 20th and early 21st.

The consequence of this centrality of the state, and of state discrimination against foreign traders, to the actual role of money – which, as we already saw, is central to capitalism as such – is that there is no such thing as a non-mercantilist capitalist state and there never can be such a thing. ‘Freedom of trade’ was a mercantilist policy in the interests of Netherlands capital in the 17th century, of British capital in the ‘long 19th century’, and is today a mercantilist policy in the interests of US capital. The nature of money, as well as the historical origin of capitalism in bulk shipping, requires that capitalism should always take the form of a hierarchy of states with a world-hegemon at its head and colonised countries at its feet. The hegemons change – from the contests of Venice and Genoa, to the Netherlands, to Britain, to the US. The hierarchy may in other respects be reorganised. But the hierarchy remains.

The result is that, since the Islamists in Iran cling to private property and markets, they cling also to the hope that, at most, they can improve the relative standing of their country within the imperialist hierarchy – as Japan did under the Meiji regime between 1867 and the 1890s, or Turkey under Atatürk in the inter-war period.

But this would not be anti-imperialist, any more than Meiji Japan was. The UK armed and helped industrialise Japan as an ally against Russia, which was thought to be threatening British India. Japan proceeded to colonise Taiwan and Korea, and in the 1930s attempted to colonise China: it had broken into the imperialist circle.

For Iran, the geopolitics of the region has excluded even such a development, ever since 1906. The Japanese in 1904 delivered for the British the destruction of tsarist Russia’s navy, and with it Russia’s east Asian aspirations. The result was a geopolitical deal. Among other agreements, the Iranian constitutional revolution, which might have led to a Meiji path, was stifled. Britain and Russia divided Iran into ‘spheres of influence’: the north to Russia, the south to Britain (reflecting Britain’s new interest in oil supplies for its navy).

Since then, geopolitics has produced industrialisation of South Korea and Taiwan as front-line US clients against North Korea and China. Iran under the shah, as a front-line state against the USSR, got some benefits of this sort. But the revolution of 1979 brought that to an end. I reiterate: such a development would (obviously) not have been anti-imperialist: it would merely have raised Iran’s standing within an imperialist hierarchy left untouched, and at the expense of other countries in the region.

The anti-US rhetoric of the Islamist regime is thus simply for domestic, and perhaps diplomatic, consumption.

Mike Macnair

First published here: https://weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1367/honouring-the-victims/